Advocating for Access to Modern Cancer Screenings

There have been more than 9.5 million missed cancer screenings in the United States as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Advancements in innovative cancer screening technologies have the potential to get Americans back on track with recommended screenings and save lives.

However, even when a new more accessible screening technology is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), it will have limited impact on improving screening rates until it is recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

The USPSTF is an independent, 16 volunteer-member advisory body that issues evidence-based recommendations on which clinical preventive services Americans should receive.2 The Task Force and their recommendations play a critical role in the health of the American population. Clinical preventive services that receive an A or B grade from the Task Force are covered with $0 cost-sharing for insured patients.3 This is an important driver of patient access and adoption of preventive healthcare as even a small co-pay has been shown to deter patients from seeking these services.4

Access to Medical Technology

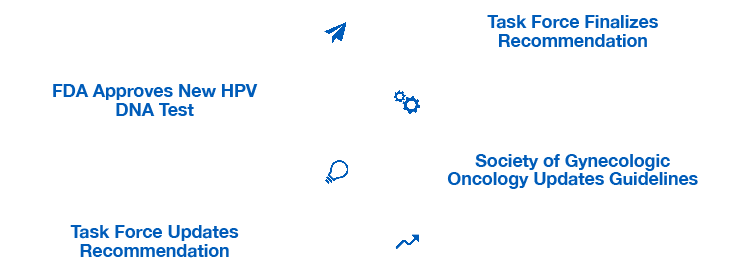

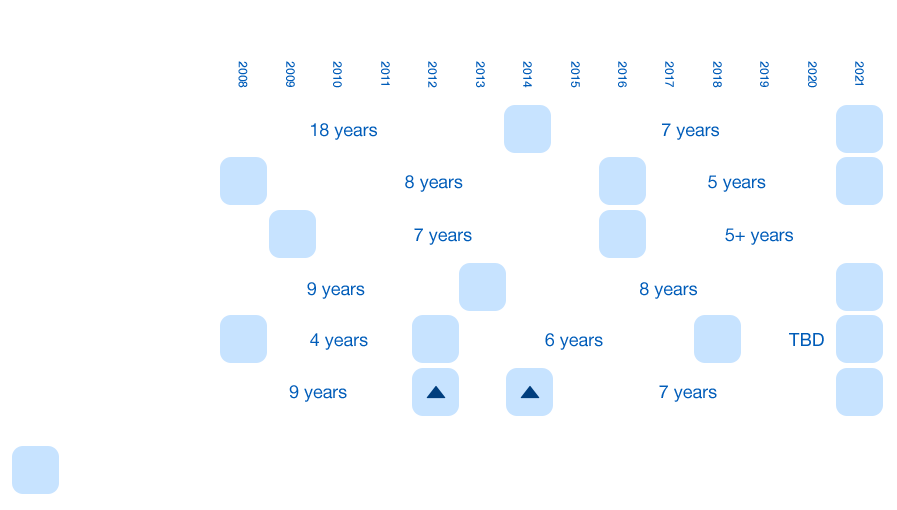

Modern medical technology moves quickly, but the frequency at which the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (Task Force) updates its recommendations doesn't reflect today's pace of innovation.

Immediate affordability of newly accessible screening tools saves lives.

Despite earlier action by other organizations, the Task Force didn't update its recommendations to reflect the innovation for multiple years.5,6

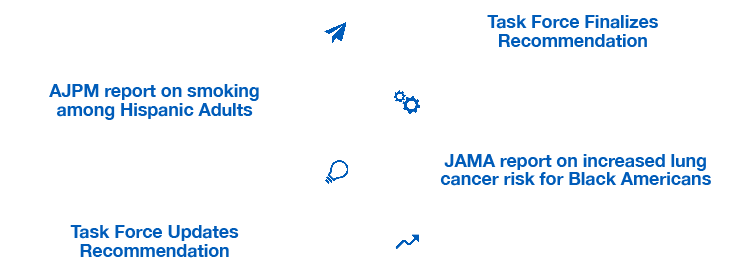

While mounting evidence showed that Black and Hispanic adults were disproportionately left out of lung cancer screening guidelines, the Task Force did not include the evidence into an updated recommendation for several years.7 Once the Task Force lowered the age and smoking threshold for screening, the number of eligible individuals in under-resourced communities nearly doubled.8

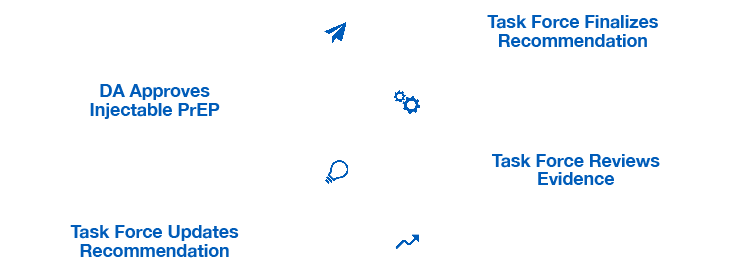

The FDA recently approved a new, long-acting version of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to reduce the risk of HIV. Despite coinciding perfectly with the regular Task Force review cycle the recommendations will not include the injectable version of PrEP for two-to-three years.*9,10

*Based on average Task Force review patterns.

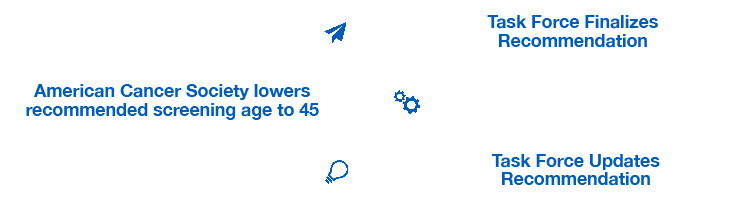

Colorectal cancer is projected to become the leading cause of cancer death for adults ages 29-49 by 2030.**11 Despite this trend, the Task Force updated its recommendation to lower screening ages three years after changes to clinical practice guidelines by the American Cancer Society.12,13

** Estimated Projection of US Cancer Incidence and Death to 2040, doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.4708

The Problem

Under its current structure, the USPSTF aims to review and update existing recommendations every five years, though multi-year delays are common.14,15 The Task Force is under-resourced and underfunded, and science sometimes moves faster than the USPSTF can review and respond.16 With rapid developments in biomedical research and innovative technologies, the current USPSTF five-year update cycle can inadvertently lead to a significant lag in the adoption of a new, promising screening technology.

A Trend That Hinders Patient Access to Scientific Advancements

Colorectal Cancer

As a current example, right now, there are large-scale clinical trials underway to evaluate the performance of blood tests to screen asymptomatic, average-risk patients for colorectal cancer.17 A blood test to detect early signs of CRC has the potential to overcome many of the access barriers associated with current CRC screening methods by incorporating CRC screening into routine medical care. However, the most recent USPSTF review of CRC screening was completed in May 202118 and the next recommendation is not expected until 2026. Therefore, once blood-based screening tests for CRC receive approval from the FDA, it may still be years until the USPSTF releases its next recommendation for CRC screening.

This has far-reaching implications: more than 75% of people who die from CRC today are not up to date with recommended screening.19 Cancer underscreening is an important factor contributing to the high cancer mortality rate in underserved populations.20 These communities disproportionately face barriers to access with current CRC screening methods, such as a lack of convenient medical facilities for screenings, transportation challenges, and jobs that lack flexibility or paid time off. Timely access to new and more accessible technologies can eliminate some of these obstacles to screening and reduce health disparities.

Frequenty Asked Questions

-

What does the US Preventive Services Task Force do?

The Task Force is an independent, advisory body that issues evidence-based recommendations on which clinical preventive services Americans should receive. The recommendations made by the Task Force address services for adults and children, and include screening tests, counseling services, and preventive medications.

-

Who compromises the Task Force? How many members serve at one time?

The Task Force is made up of 16 volunteer members who are nationally recognized experts in prevention, evidence-based medicine, and primary care (family medicine, geriatrics, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology and mental health). The panel is led by a chair and two vice chairs.

-

Task Force members are appointed by the Director of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to serve 4-year terms. New members are selected each year to replace those members completing their appointments. Anyone from the public can self-nominate or nominate someone else to serve on the Task Force. Task Force members are screened to ensure that they have no substantial conflicts of interest that could impair the scientific integrity of the Task Force's work.

-

Prior to passage of the Affordable Care Act, health plans could voluntarily take into account Task Force recommendations for coverage of clinical preventive screenings. After passage of the Affordable Care Act, all individual and group health plans must cover clinical preventive services that receive an A or B rating from the Task Force with $0 cost-sharing for the patient. In the wake of this change, some studies showed that the utilization rate of preventive services increased for privately insured individuals.22 CMS also has the authority to require coverage for preventive services recommended by the Task Force, but the agency is not required to do so.

-

How often does the Task Force meet?

Historically, Task Force members meet three times a year for 2 days in the Washington, DC area. AHRQ estimates that members devote approximately 200 hours a year outside of in-person meetings to their Task Force duties, including conference calls and email discussion to prioritize topics, design research plans, review and comment on systematic evidence reviews, discuss and make recommendations on preventive services, review stakeholder comments, draft final recommendation documents, and participate in workgroups on specific topics and methods.23

-

Where does their funding come from? How much funding do they receive?

Congress appropriates the budget for AHRQ and includes funding for administration of the Task Force. In Fiscal Year 2022, Congress appropriated $11.542 million for the Task Force, the same level of funding that was appropriated in FY2021. The President's FY2023 Budget included level funding for the Task Force.24

-

AHRQ provided the Task Force with a budget of $11.542 million in FY 2021. These funds allowed the Task Force to post 12 draft recommendations and finalize 8 recommendation statements. The Task Force estimated that under level funding in FY2022 it will conduct evidence reviews and make recommendations on 10-12 topics.24 Limited resources are noted as one of the reasons the Task Force is limited in its capacity to make more updates, however it is unclear exactly how much more additional funding would be required to conduct more regular reviews and updates. In the AHRQ FY 2023 budget justification, the USPSTF notes that “the cost for evidence reviews has increased over time, therefore, with the same level of support the USPSTF may complete fewer evidence reviews each year.”25

-

FDA has no oversight authority over the Task Force. The Task Force is an independent advisory board not subject to direction by political appointees, other agencies, or Congress.

AHRQ, which is subject to Congressional and HHS oversight, provides ongoing administrative, research, and technical support for the operations of the Task Force, including coordinating and supporting the dissemination of the recommendations of the Task Force, ensuring adequate staff resources, and assistance to those organizations requesting it for implementation of the Guide's recommendations.

The Task Force does consider best practice recommendations from the AHRQ, NIH, CDC, the Institute of Medicine, specialty medical associations, patient groups, and scientific societies in making its recommendations. The Task Force also outsources some of the reviews to ACIP and HRSA in instances where they have an expertise.

-

Have there been any reforms by Congress to change the Task Force?

The Task Force has been modified multiple times since it was first created in 1984, most notably in 1998 and 2009. In 1998, the Public Health Services Act was amended to give AHRQ oversight of the Task Force and the responsibility to provide ongoing administrative, research, and technical support. In 2009, the Affordable Care Act mandated that all individual and group health plans cover clinical preventive services that receive an A or B rating from the Task Force with $0 cost-sharing for the patient.

-

What is the process by which the Task Force selects their topics for review?

Anyone can nominate a new topic for review at any time. The Task Force reviews nominated topics for relevance to and impact on prevention, primary care, and public health.

-

How long does it take for the Task Force to review a topic?

Current law requires the Task Force to review topics every five years. While there are some exceptions, the Task Force often takes longer than the stipulated time to update their recommendations. A survey of a dozen recent USPSTF recommendations, including lung cancer, STD screenings, and others found an average seven-year interval before the most recent update was issued.26

-

What does the process entail once a topic is selected?

Once a topic is prioritized for review, the Task Force develops a research plan and seeks expert input. The Task Force then posts the draft research plan to their website for public comment. Once the Task Force reviews all comments, they revise and finalize the research plan.

The Scientific Director working with an Evidence-based Practice Center then analyze peer-reviewed evidence to draft evidence for the Task Force to review. The Task Force then reviews the evidence and develops a draft recommendation statement. The draft is posted on its website for public comment.

Finally, comments are reviewed, the draft recommendation is adjusted, finalized, and published in a peer-reviewed journal.27

In the case of the latest colorectal cancer screening guidelines, the research plan phase took 6 months, the development and posting of a draft recommendation took 17 months, and finalizing the recommendation based on public comments took 8 months.28

-

What does a Task Force recommendation look like?

Task Force recommendations offer a letter grade that concisely summarizes the strength of guidance and the quality of the evidence supporting conclusions. Preventive services with the highest two grades, A or B, are covered by most insurance plans without additional copay for a beneficiary, which removes a major barrier to care. Recommendations also include an extensive summary of the scientific evidence the committee reviewed in reaching its conclusions and are published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

-

Can the Task Force quickly change or amend a recommendation if new scientific evidence comes out?

The Task Force does not have a statutory process to amend or alter a recommendation at any time but could choose to expedite a review. However, in practice the Task Force rarely updates or alters recommendations prior to the five-year window required under law.

-

The Task Force states that it may consider public comments, including stakeholder groups, at points in their update process. Additionally, the Task Force website provides a list of stakeholders that it may turn to contribute expertise and assist with distributing recommendations. The Task Force does not publicly comment on what public input they have received or considered for their final recommendations.

-

The Task Force does publish preliminary drafts of their recommendations and research plans for public input before finalization. The public may also submit comments calling for the Task Force to review new or existing guidelines. However, the proceedings and deliberations of the Task Force are not visible to the public.

-

In the last decade there have been only 3 approvals that fall under an existing taskforce recommendation.29,30 In 2014, a stool-based DNA test for colon cancer screening and the first HPV test for cervical cancer screening were both approved.31 1 injectable drug to prevent HIV infection was approved in 2021 and the Task Force began a draft research plan in November of 2021.32 Given Task Force history, we can expect that it will be a few years before final guidelines that include the new drug may be posted.

The FDA publishes novel drug and device approvals each month on their website, so this information is readily accessible to both the public and the Task Force.